1921 photo of the island of Castellorizo (Castelrosso in Italian) of the Rodi archipelago. It was the only Italian colonial territory in the Middle East geographical region, being located south of Anatolia near Adalia (actual Antalya).

Indeed Italian colonial expansion began shortly after the country’s unification in 1861. From the very start, the overseas possessions that liberal Italy managed to acquire were positioned on the edges of the Middle East. During the 1870s and 1880s the Italians were able to establish themselves on the southern end of the western shores of the Red Sea, a process facilitated by British acquiescence and at times even their support. In 1885 Italy’s Foreign Minister, Pasquale Mancini, justified the necessity of this remote colony, which came to be known as Eritrea, by arguing that the Red Sea provided the key to the Mediterranean.

In the Mediterranean itself Italian expansion was much slower to develop. In 1880 the prominent Italian statesman Francesco Crispi told the Chamber of Deputies that modern Italy must learn from the history of ancient Rome and the medieval city-states and assert itself in the Mediterranean. Italian politicians coveted Tunisia but in 1881 their ambitions were frustrated by the French who occupied that country and established a protectorate over it.

Soon afterwards Egypt fell into the hands of another international Power, Great Britain. In the late 1870s and early 1880s Italy sought to partake in the international management of Egypt. Of all the European communities in this country the Italian was second in size only to the Greek. In July 1882, when the Urabi Revolt threatened European interests in Egypt, Britain invited Italy to participate in its intervention there. Mancini, however, refused, fearing the costs of the enterprise, the military difficulties it entailed, as well as German and French reactions. The paper Popolo Romano called on the Italian government not to exceed in shyness and to intervene. A little of the African sun, they argued, would do no harm to Italy’s soldiers. After the British succeeded in overcoming Egyptian resistance with ease, Italian opposition leaders such as Crispi and Sidney Sonnino lamented the loss of a colonial opportunity.

Expansionist ideas suffered a setback following Italy’s defeat by the Abyssinians at Adowa in 1896. Nonetheless, during the first decade of the twentieth century the idea of colonial expansion began to gain ground in certain sectors of Italian society. In 1906 the "Istituto Coloniale Italiano" in Rome was established along with the journal "Rivista Coloniale" which disseminated patriotic ‘colonial culture’. The Associazione Nazionale Italiana held its first congress in Florence in December 1910 and soon began to publish the weekly "L’Idea Nazionale". Literary figures like Gabriele D’Annunzio, Giovanni Pascoli, Alfredo Oriani and Enrico Corradini promoted expansionism and revived the myth of Italy’s glorious Roman and Venetian past. Expansionist-nationalist ideas were flourishing among the younger cadres of the Foreign Ministry and the term "Mare Nostrum" (our sea), as a way to describe the Mediterranean, was put into use before the First World War.

General Allenby made his historical entrance in Jerusalem on December 11, 1917. He had at his left L. Colonel D'Agostino, commander of the Italian detachment of Bersaglieri in Palestine. It was the first time since the Crusades that the Holy City was in Christian control.

As Christopher Seton-Watson has pointed out, Italian imperialism was largely imitative. The ‘industrial imperialism’ of northern Italy’s traders, bankers and manufacturers took the form of a search for markets, natural resources and investment opportunities, while the ‘ demographic imperialism’ of southern politicians, publicists and peasants took the form of a search for land where Italy’s surplus population could be settled in prosperity while still remaining under the Italian flag. Eventually, both economic and demographic justifications for imperialism proved unfounded. Italian industrialists and bankers did have commercial interests, for instance, in the Ottoman Empire, but it was often the government in Rome that had to encourage them to take steps that would be useful to the ambitions of Italian foreign policy. In the Italian case capital usually followed the flag, not the other way around. Even under Fascism, Italy’s economy gained more from tourism than it did from speculation in the Middle East. Furthermore, Italian capitalism showed little inclination to invest in the colonies without government subsidies or guarantees. The colonies were a constant strain on the national budget and none of them paid their own way.

As far as Italian emigrants were concerned, the USA and even French Tunisia remained far more appealing destinations than Eritrea, Somalia and, later on, Libya. However, an expansionist policy and the pursuit of colonies enabled Italy to maintain its posture as a Great Power. Moreover, foreign policy provided help for patriotic unity, enabling a rare collaboration between the lay Italian state and Catholic sectors close to the Vatican. Religious organizations such as the Salesian order and financial institutions with connections to the Papacy such as the Banco di Roma were harnessed to enhance the prestige of Italian culture and further the country’s commercial interests on the southern and eastern shores of the Mediterranean. As the Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann noted some years later, ‘in Palestine the Vatican and the secular Italian Government seem to be identical. The cleavage which exists in Rome is not apparent in Jerusalem’. Step by step nationalist politicians, diplomats, Italian clergymen and businessmen of the Liberal era laid the foundations that later served the Fascist regime’s Middle Eastern policy.

In 1911 favourable international conditions as well as nationalist sentiments in the Chamber of Deputies and in the press combined to persuade the Prime Minister, Giovanni Giolitti, and his Foreign Minister, Antonio di San Giuliano, to seize a Mediterranean colony for Italy and perhaps help assert the country’s claim to be a Great Power. The invasion of the Ottoman provinces of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica was launched in late September 1911. The Italians miscalculated the resistance they would encounter and expected a quick victory. Much to their surprise, the local Arab and Berber population joined the Ottoman forces in resisting the invasion, pinning the Italians to their positions near the coast. In January 1912 Sayyid Ahmad al-Sharif, the leader of the Sanusiyya, a religious Islamic order that was founded in the nineteenth century and had a strong following in Cyrenaica, proclaimed a "Jihad" against the invaders. In order to break the deadlock and to exert more pressure on the Ottomans, the Italians resorted to capturing the Dodecanese Islands in the Aegean in April 1912, to employing their navy in the Dardanelles, and to bombarding Beirut in Lebanon and the port of Hodeidah in the Red Sea. The Italian government also began to send money and arms to support the revolt of Sayyid Muhammad Ibn Ali al-Idrisi against the Ottomans in Asir in the Arabian Peninsula. The military and diplomatic impasse was only solved when the outbreak of the First Balkan War in October 1912 forced the Ottomans to capitulate.

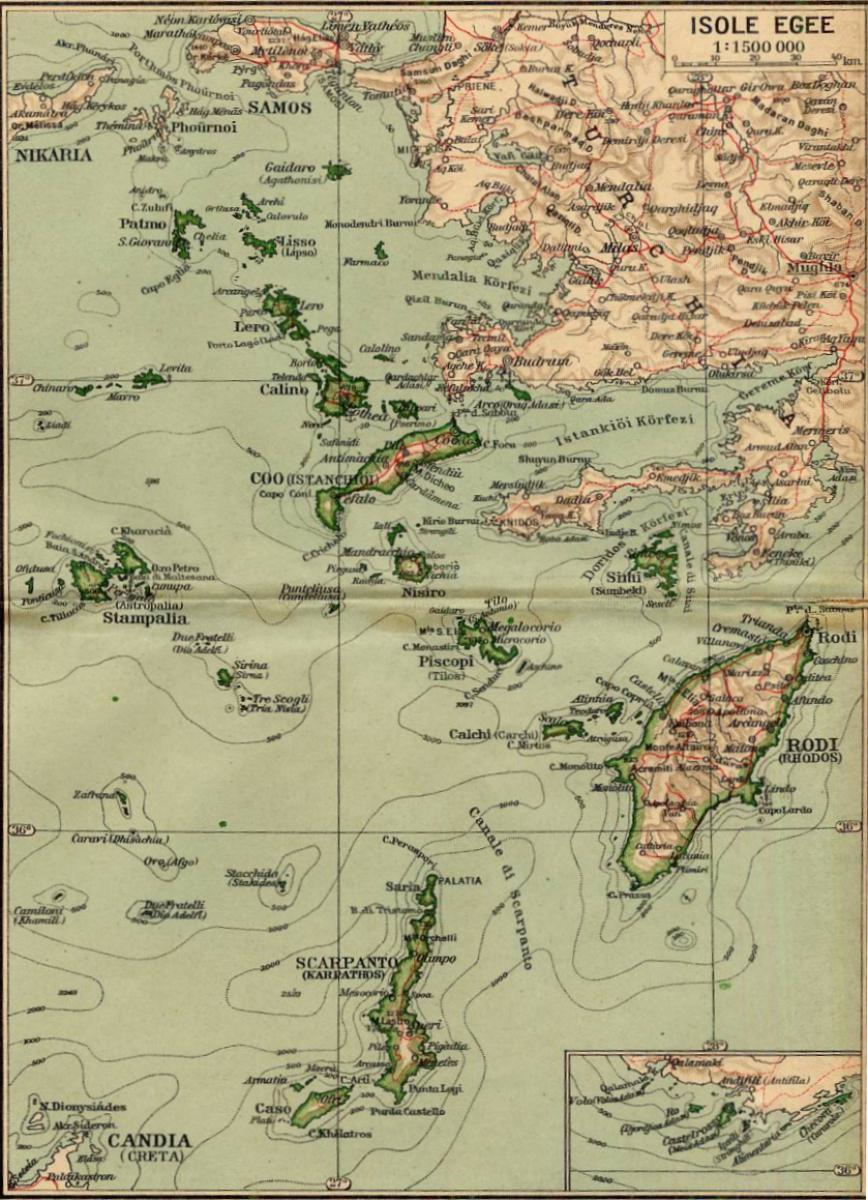

|

| Map of "Dodecaneso italiano", called also "isole egee italiane" |

In addition to acquiring Libya, the Italians gained temporary custody of the Dodecanese which, after the First World War, became permanent.

Though the Libyan War had been more successful than the disastrous campaign in Ethiopia 16 years earlier, it re-asserted the pattern that was to continue through to the Fascist period, whereby colonial expansion was ruinously expensive and rife with setbacks.

In 1912–14 Italy began to seek commercial concessions from the Turks in Asia Minor, especially in the region of Adalia (now known as southwestern Anatolia). However, these plans were thwarted by the outbreak of the First World War.

Another sphere where Italy sought to assert its influence was on the eastern shores of the Red Sea, in close proximity to the colony in Eritrea. Italian attempts at commercial penetration in southwestern Arabia began as early as 1910. Rome’s ambitions in the region sparked a Red Sea rivalry with Britain which would last, with varying degrees of intensity, for three decades.

With the outbreak of the First World War in Europe new horizons were opened for Italian colonial expansion. In November 1914 the Ministry for the Colonies, which was established at the end of the Libyan War, charted out Italy’s colonial aspirations. In North Africa Italy sought, among other things, a British concession of the Jarabub Oasis on the Egyptian-Libyan frontier. In the Arabian Peninsula Italy wanted a position of parity with Britain: either a joint guarantee of Arab independence or – if Britain were to establish itself in Arabia – the Italians ought to be allowed to acquire a similar position in Asir and parts of Yemen. An article which appeared in Rivista Coloniale in January 1915, and was probably inspired by the Ministry for the Colonies, called for the conquest of Hodeidah, Mokha and Sheikh Said on the eastern shores of the Red Sea in order to prevent the region from falling to another power. Middle Eastern ambitions played a part in the Italian decision to enter the First World War. In February 1915 the British and French fleets bombarded the Dardanelles. The Italian Prime Minister, Antonio Salandra, and his Foreign Minister, Sidney Sonnino, feared that if Italy did not join the war soon it would arrive too late to take part in the defeat and partition of Turkey. Despite their former membership in the Triple Alliance, the Italian government approached the British, in early March 1915, with a list of conditions for Italian entry into the war on the side of the Allies. Some of the recommendations of the Ministry for the Colonies were included in Italy’s colonial demands: equitable treatment in the Mediterranean; a mutual Anglo-Italian guarantee for the independence of Yemen and the Muslim holy places as well as an undertaking not to annex any part of the Arabian Peninsula; and an extension of Italy’s colonies in Eritrea, Somalia and Libya through concessions from the colonies of Britain and France. However, Italy was hardly in a strong position to bargain over colonies, having during the winter of 1914–15 lost control of all Libya except for some positions near the Mediterranean coast.

The Treaty of London, which was signed on 26 April 1915 and would soon bring Italy into the war, gave a vague assurance that Italy ‘ought to obtain a just share of the Mediterranean region adjacent to the province of Adalia’. Article 13 of the treaty stipulated ‘in principle that Italy may claim some equitable compensation’ in Africa should France and Britain increase their colonial territories at the expense of Germany. Italy did not obtain the mutual Anglo-Italian guarantee it sought for the Arabian Peninsula. Instead Rome adhered to an existing pact between the allies, according to which the Muslim holy places in Arabia would remain under the authority of an independent Muslim power. The promises Italy was given in the Treaty of London were never fully fulfilled and for many years this failing was used by Italian statesmen to justify their colonial claims.

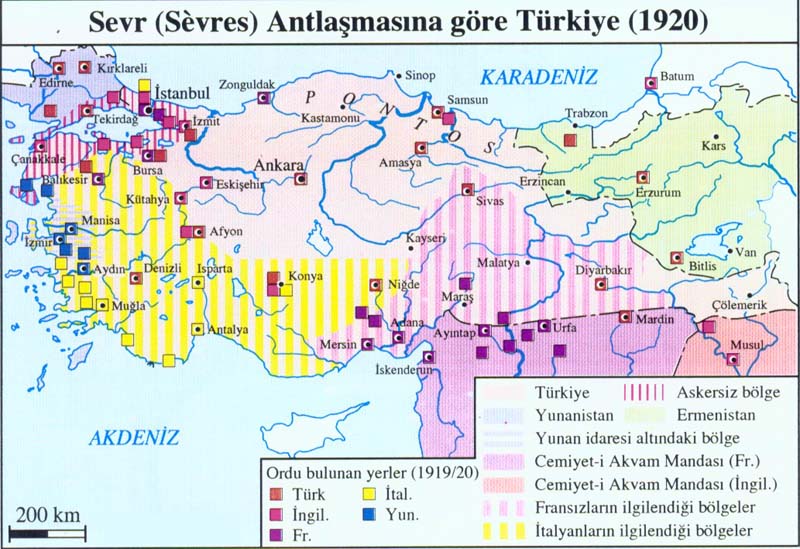

1920 Map showing in yellow the Italian area of influence in Anatolia, according to Sevres Treaty

Despite Italy’s declaration of war on Turkey in August 1915, the SykesPicot agreement, which partitioned the Middle East into British and French spheres of influence, was concluded in early 1916 without Italy’s knowledge. The agreement made no mention of Italy. Furthermore, in Article 10 of Sykes-Picot, the French and British agreed that no power would be allowed to acquire territory in the Arabian Peninsula or to build naval bases on the Red Sea islands, a clause that could be interpreted as anti-Italian. Indeed, the British Foreign Secretary Edward Grey and other senior Whitehall officials believed even before the war that ‘it is of great importance not to allow Italy to obtain a foothold on the Eastern coast of the Red Sea or the adjacent Islands.’ When Sonnino learnt of the existence of the Sykes-Picot Agreement he was alarmed. The text was finally disclosed to the Italians in October 1916, only after Sonnino – a staunch supporter of Italy’s participation in the war – threatened to resign. In the following months Italian wartime diplomacy sought to modify the terms of the Anglo-French agreement, adjusting them to Italy’s aspirations. Sonnino’s policy was epitomized by the slogan ‘O tutti o nessuno’ – either everybody gets a piece of the Ottoman Empire or nobody does. Finally, the St Jean de Maurienne Agreement of April 1917, which was later embodied in an exchange of letters on 18 August 1917, saw the Allies recognize Italy’s sphere of influence in Asia Minor (which was to include Adalia, Smyrna and Konia). Sonnino was also able to further Italian aspirations in the Holy Land.

According to Sykes-Picot, Palestine west of the Jordan River and exclusive of Haifa and Acre was designated to be administered internationally. In 1917 the Allies recognized Italy’s claim to participate in the country’s administration. On the other hand, an Italian claim for the Farsan Islands in the Red Sea was not recognized. The agreement seemed to improve Italy’s cards for the post-war peace settlement. However, it was dependent upon Russian ratification and as this was never given, Britain was able to renounce the obligations it had undertaken at St Jean de Maurienne once the war was over. Sonnino attempted to bolster Italy’s tenuous diplomatic position in various ways. In view of the fact that many of Italy’s subjects in Libya and East Africa were Muslims, he argued that, as a ‘Muslim Power’, Italy should be informed of any agreements made with the Sharif of Mecca. As the resistance to Italian rule in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica had a distinct Islamic flavour, Rome sought the friendship of the rulers of the Muslim holy places in Arabia. Sonnino repeatedly offered to send Muslim Italian colonial troops to join the Hijaz expedition but was continually turned down by the British.

The Foreign Minister was partially more successful when it came to ensuring Italian participation in the Egyptian Expeditionary Force. In early March 1917 he learnt that the French were planning to send troops to take part in the conquest of Palestine. The Italians had a vested interest in the Catholic institutions which operated in the Holy Land and Sonnino was eager to participate in the country’s post-war international administration. Seeking not to be outdone by the French he offered the British government to send 5,000 troops. On 9 April 1917 the British reluctantly agreed that a small Italian detachment of ‘some three hundred men’ could join the expeditionary force ‘for representative purposes only’. Despite the opposition of Italy’s obstinate Chief of Staff, a small Italian detachment left for Port Said in May 1917 and eventually took part in the Allied offensive against the Turks at the Third Battle of Gaza. In the summer of 1918, when General Allenby was prepared to accept a more substantial Italian contingent, Sonnino tried to persuade his government to increase Italy’s participation in the war effort in the Middle East. He argued that such a move would strengthen Italy’s claim to receive territory in Asia Minor. However, he was unable to persuade Italy’s generals or the Minister for the Colonies to deliver the troops he requested. In September 1918 Allenby advanced on northern Palestine and Syria without making use of Italian forces. Italy’s poor military performance on the one hand and Wilsonian ideals of self determination and adjusting state frontiers according to lines of nationality on the other, did not create an atmosphere favourable to the furtherance of Italian colonial claims once the war was over. At the peace conference Italy fared badly.

The Farasan islands of Saudi Arabia (facing the Dahlak islands of Italian Eritrea) were requested by the Italians as compensation for their intervention in WWI, but the UK did not accepted the proposal in order to maintain the full Arabian peninsula under British control

The Italians’ request to receive the Farasan Islands in the Red Sea as part of their colonial compensation was turned down by the British Colonial Minister, Lord Alfred Milner (the Farasan islands were a border territory of the Roman empire, as evidences of roman legionaries presence have been discovered on the main island; if interested, read Romans in Farasan islands

The landing of Italian troops in Adalia and Smyrna in spring 1919 aggravated the already tense relations between the Italian delegation to Paris and the Allied leaders David Lloyd George, Georges Clemenceau and Woodrow Wilson. Eventually, the Italians had to abandon the hope of acquiring territories in Asia Minor. Italy’s post-war Prime Minister, Francesco Nitti, believed that colonial adventures in the Middle East at this stage ‘would have involved Italy in undoubted economic ruin and in the certainty of military adventures of incalculable difficulty, which would have absorbed all the resources of the country at the very time when Italy had most need of them.’ Following the rise of Mustafa Kemal’s nationalists, the Italians withdrew their forces from Asia Minor and opted to establish friendly relations with the new regime in Turkey.

But with the rise of Mussolini's fascism the Italian policy in the Middle East started to be more aggressive and the moderate approach of liberal Italy to those territories disappeared after 1922. In nearly a dozen years more, fascist Italy would attack Ethiopia and create the "Italian empire": but no region of the Middle East was conquered or even controlled by Mussolini, even if he did a tentative in Yemen in the 1930s. Indeed senator Giacomo Gasparini (former governor of Italian Eritrea) in 1937 signed an Italian Treaty with Yemen -that should have worked for 25 years- and declared: "Yemen has now for Italy the same satellite-state position in the Red sea as Albania had in the Adriatic sea". So, probably without WW2 (we must remember that Mussolini initially in 1939 wanted to postpone the global war of Hitler at least until 1942) the Italians would have done soon or later in Yemen the same occupation/annexation they did in Albania in 1939.

.jpg)